Recovery from a crisis event is a long-term process best guided by a representative leadership team. These resources are designed to support families, educators, schools, districts, and states throughout the phases of crisis recovery following a significant crisis event that disrupted the learning environment.

The following guiding principles will support coordination and response efforts. If your district or state is looking for external support or technical assistance for crisis prevention, preparation, response, or recovery, please contact your state PBIS coordinator.

The educational cascade describes the bi-directional relationships between states, districts, schools, classrooms, and ultimately students. Each level supports and is informed by the others. Crisis incidents vary considerably with respect to impact, and disruptions or stress at one level of the cascade can have ripple effects on the others. Effective response efforts include carefully and continuously assessing strengths and needs to provide appropriate supports across the full cascade.

A crisis event, by definition, overwhelms local response capacity. Therefore, non-local (e.g., state-level, regional, nongovernmental) supports are both critical and warranted. However, these additional supports should be designed to supplement and support rather than replace local response efforts. Additionally, any non-local supports would ideally include plans for building long-term local capacity and fading external involvement over time. Response efforts should be team-led to reduce fatigue and burnout and ensure stability in recovery efforts in the event of leadership turnover. A key goal of the augmented response team is to support local leadership in identifying school and community strengths and building confidence in implementing recovery supports that are closely aligned with the local context and culture and produce meaningful outcomes. This team should also coordinate outside assistance efforts to minimize disruption to teaching and learning

Crisis response efforts must support both the disrupted systems and the impacted individuals working within that system. Recovery for impacted individuals may not be linear and is unique to each person. Response teams should expect variability in local leadership capacity and may need to slow or pause planned meeting agendas or implementation actions to provide space for impacted individual recovery. Response efforts can support individual recovery by promoting engagement in activities supporting resilience by building or strengthening connections with others, reorienting to an overall purpose, practicing adaptability or creativity, rebuilding hope through small achievable goals and actions, and seeking more intensive support as needed. Recovery efforts will need to continuously consider a balance between actively directing actions to support recovery goals and building confidence in local leaders. For example, at times response team members may increase structure and guidance for district actions, while at other times it may be more helpful just to listen and prioritize building trusting relationships to better understand the local context and individuals affected by the crisis.

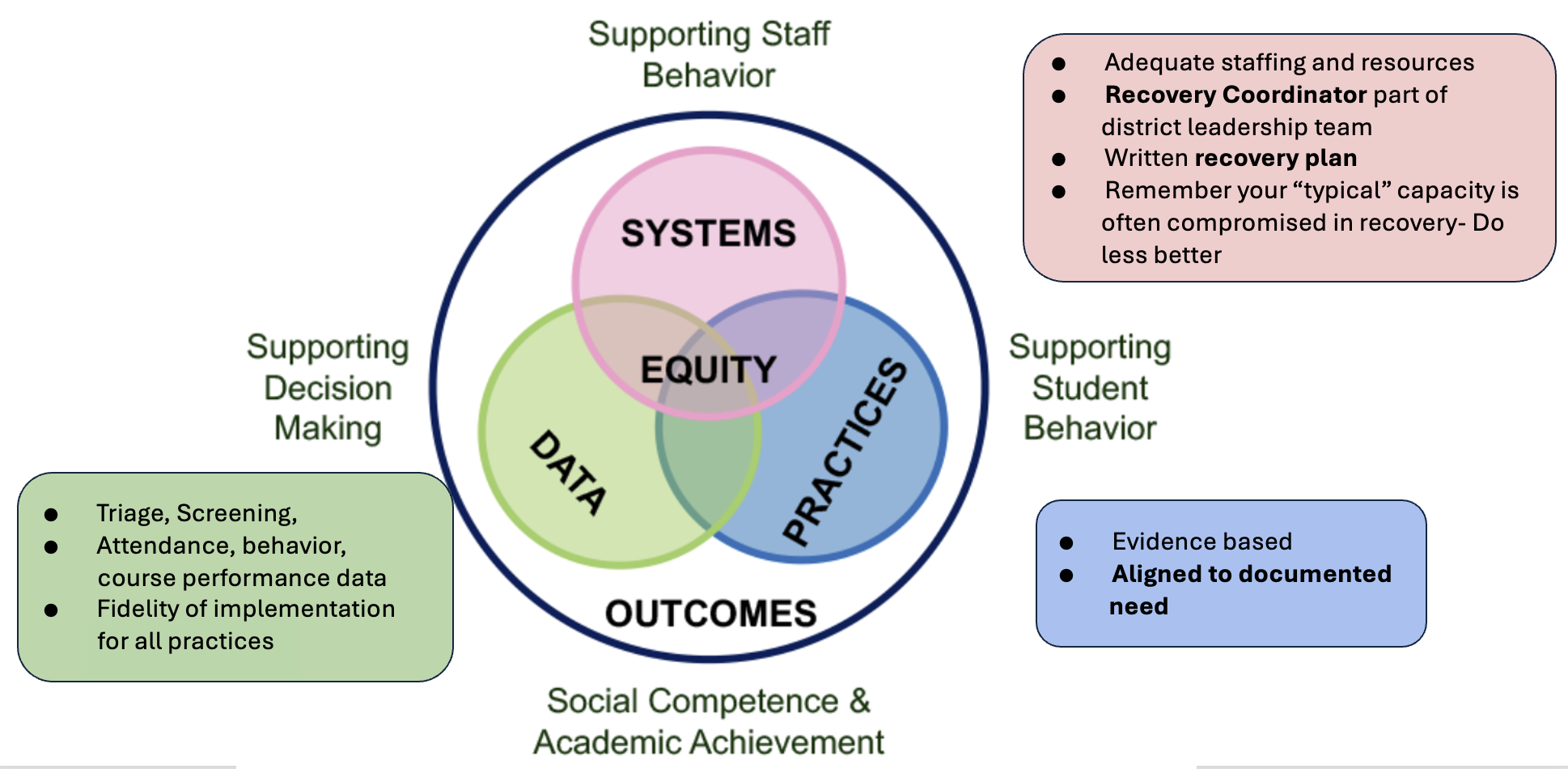

The multi-tiered logic provides a foundation for organizing response and recovery efforts that can be aligned with existing state multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS). The equitable implementation of systems to support implementation capacity, practices to support students and data to guide decision making can improve the efficiency and effectiveness of response and recovery efforts. At each phase in recovery, teams should consider supports needed for all students, staff, or families (Tier 1); supports needed by specific groups of students, staff, or families (Tier 2); and individualized or intensive supports needed by a few students, staff, or families (Tier 3). By organizing supports in this way, leadership teams can reduce the need for more intensive supports by meeting needs more proactively. Identifying clear outcomes for recovery activities, systems to support implementation capacity, evidence-based practices to support students, and using data to guide implementation. Supports should be adapted as conditions change across phases of recovery [link to resource?]. Teams can use general instructional principles to inform options for intensifying supports. Supports can be adjusted by making them more (a) explicit or directive, (b) focused (e.g., critical content or immediate next steps only), (c) interactive (e.g., increase opportunities for participation or feedback), or (d) connected (e.g., incorporating individual interests or learning histories).

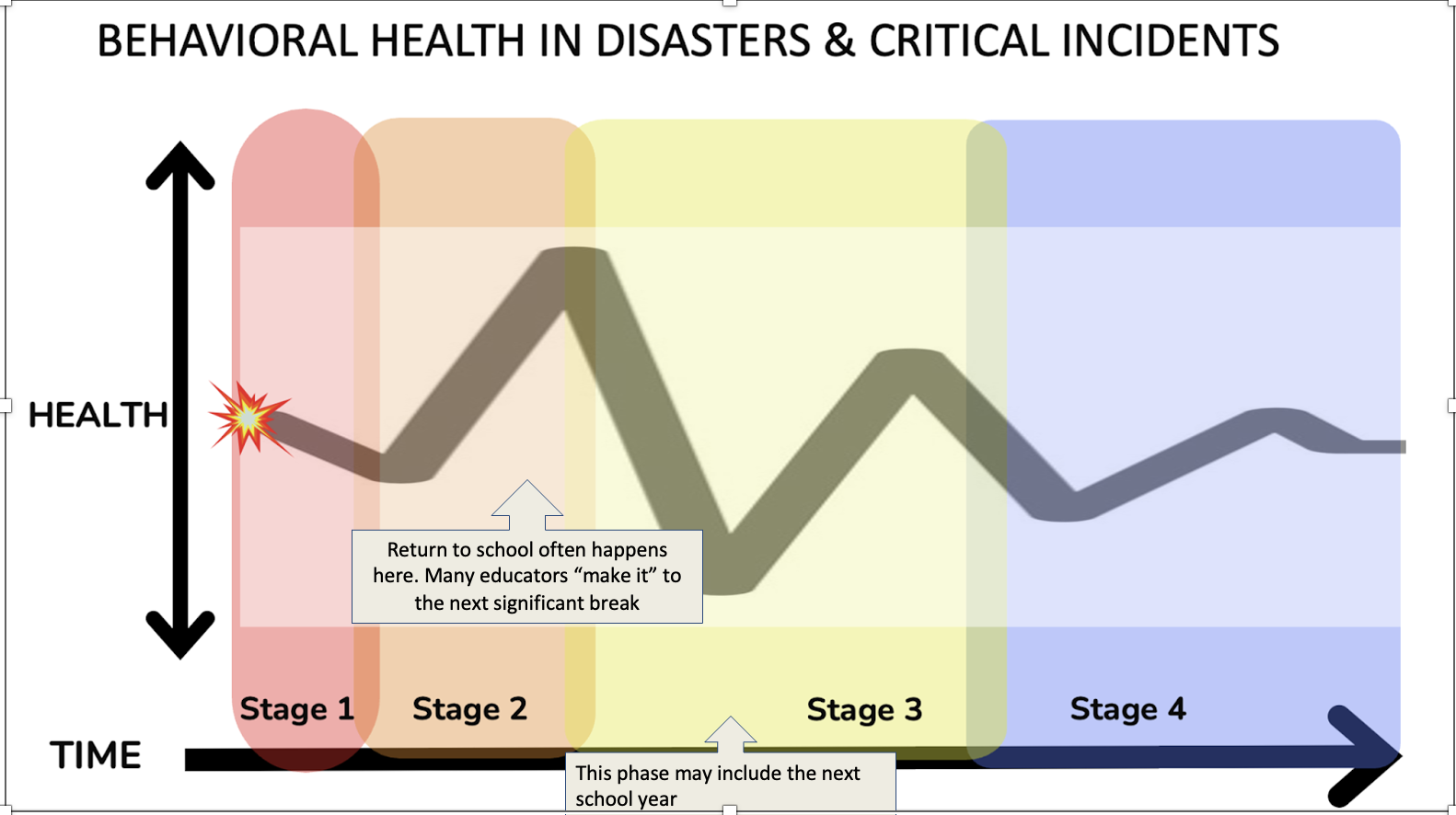

While everyone’s path to recovery is unique based on individual differences, there are community and population-level trends that we can use to predict levels of need across time and guide recovery planning (Adapted from Mauseth, Covington, Chan, Frazier (in preparation).

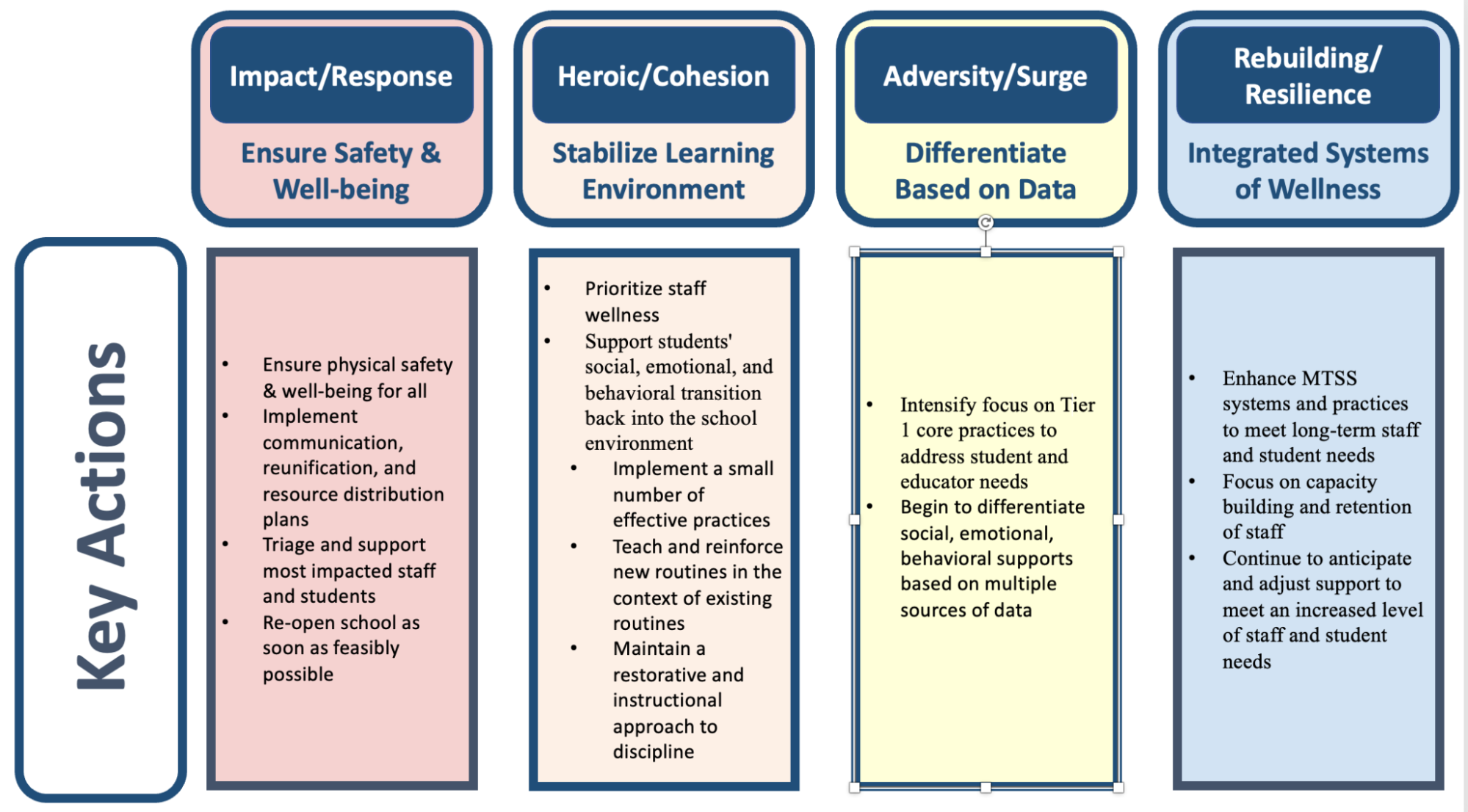

This figure briefly describes each phase and key actions. We provide expanded descriptions of each phase and key actions with resources below.

This phase begins with the onset of the crisis event and encompasses the time during which schools are closed or significantly disrupted. Following the immediate responses, the school and district must begin planning for reopening. The primary goal during this time is to ensure safety and focus on the well-being of students, staff, and families. This phase occurs hours to weeks post-incident.

Common responses may include difficulty concentrating, sleep disturbance, separation anxiety, hyperactivity, and crying spells. These symptoms in the first few weeks following a traumatic event are normal. Symptoms at this point are not indicative of longer-term challenges and can be addressed as normal responses to the grief and compromised safety that was experienced. Crisis events affect everyone differently. Students who have struggled in school before the crisis event may need more intensive support in this phase.

This phase generally begins when schools re-open as the district transitions from rescue to initial recovery. Resources are directed toward social, emotional, and behavioral supports and the goal is to stabilize the learning environment and promote a sense of community for healing. This phase occurs weeks to months post-incident.

Social cohesion and external support are strong during this phase and community members may have an unrealistic perception of recovery and the extent of the impact.

This phase occurs months post-incident and may include the start of the next school year. The goal during this time is to use data to begin to differentiate supports and plan for long-term recovery.

This is a challenging phase during which much of the immediate sense of social cohesion and outside support may fade. Social, emotional, and behavioral needs are likely to increase in both acuity levels and number of people needing support. Educators, students, and family members may experience increased levels of exhaustion, grief, loss, and hopelessness. Because everyone moves through the recovery process at different rates, community cohesion may be eroded as some community members are “ready to move on” while others are still really struggling. Depression or suicide ideation or attempts may increase during this time.

During this phase school districts develop an enhanced full continuum of supports that meets the ongoing needs of staff and students and use data to monitor progress and match supports to existing and emerging needs. This phase occurs months to years post-incident. The goal is to establish a culture of wellness grounded in community connections and collaboration.

Educators, students, and family members may experience reconnection, adjustment, and a renewed sense of purpose and hope. Exhaustion, grief, and loss may continue for some. Disaster cascade effects may occur if additional traumatic incidents impact individuals or the community.